In the 1980s, the coastal fishing town of Prince Rupert is booming. There is plenty of sockeye salmon in the nearby ocean, which means the fishermen are happy and there is plenty of work at the cannery. Eleven-year-old Mia and her best friend, Lara, have known each other since kindergarten. Like most tweens, they like to hang out and compare notes on their crushes and dream about their futures. But even though they both live in the same cul-de-sac, Mia’s life is very different from her non-Indigenous, middle-class neighbor. Lara lives with her mom, her dad and her little brother in a big house, with two cars in the drive and a view of the ocean. Mia lives in a shabby wartime house that is full of relatives—her churchgoing grandmother, binge-drinking mother and a rotating number of aunts, uncles and cousins. Even though their differences never seemed to matter to the two friends, Mia begins to notice how adults treat her differently, just because she is Indigenous. Teachers, shopkeepers, even Lara’s parents—they all seem to have decided who Mia is without getting to know her first.

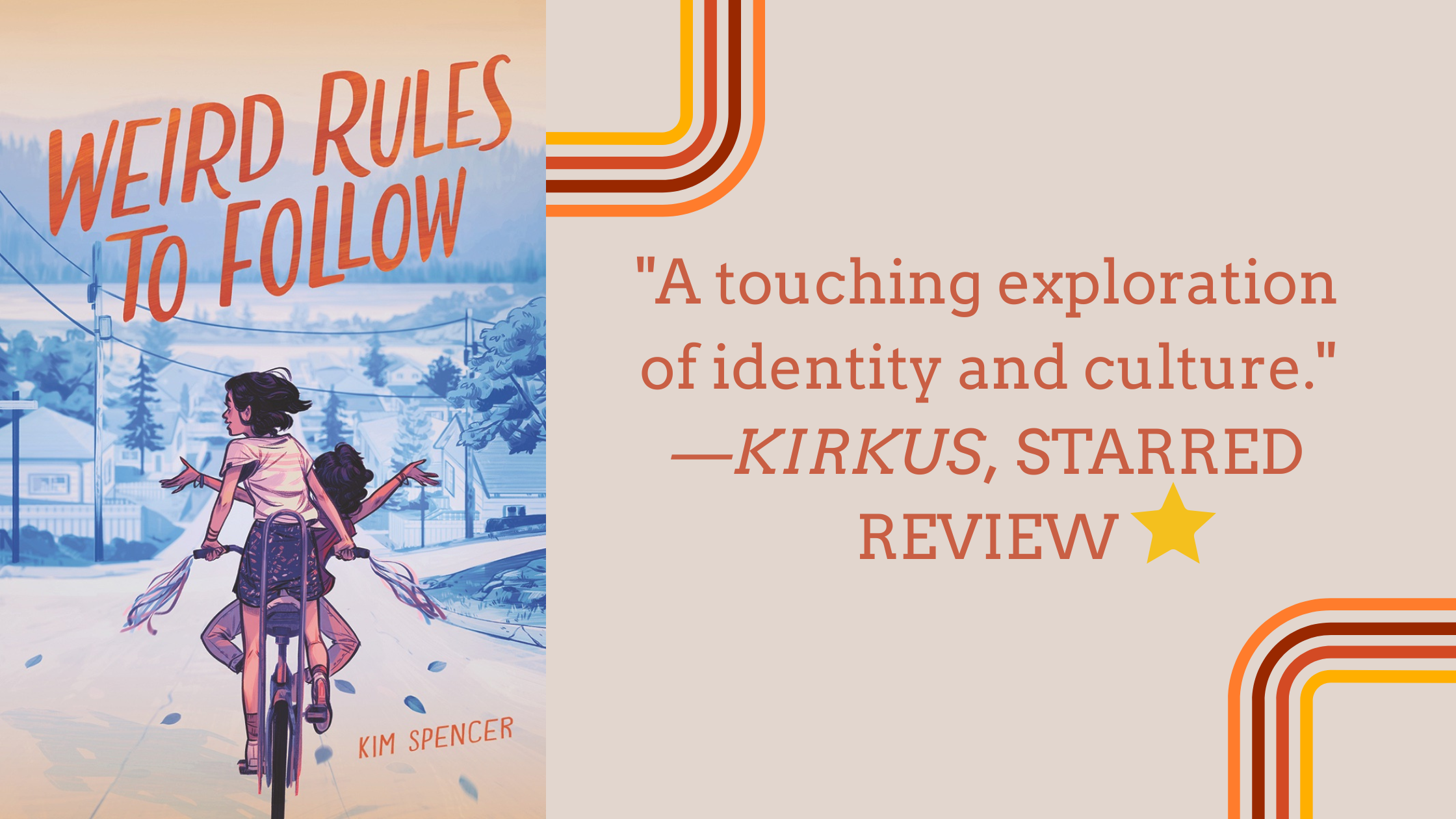

Weird Rules to Follow by Kim Spencer is releasing on October 18, 2022. Told in vignettes, this captivating novel for middle-grade readers explores the complexities of growing up and the toll that it can take on childhood friendships. Read a sample chapter below!

Salmon Season, 1985

Prince Rupert is well known for rain and fishing. I’ve never known anything but. Like rain, salmon has always been a part of my life—in the ocean, on the stove, in the refrigerator or in my belly.

Most people say they like summer for the sun, but for coastal Natives, summer means one thing—salmon. The sockeye salmon season. It’s an important time of year because that is how most Native people earn their living. It’s also when we preserve our food for the winter.

Our small town begins stirring with excitement as Native people from surrounding villages arrive. Third Avenue bustles with cars and people. The adults seem happier when they are busy and there’s work to do. The men go out commercial fishing, and the women (my mom and aunties included) put in long, hard hours at the fish cannery, which runs shifts around the clock.

It’s the middle of summer. I go to visit my mom at the cannery on her lunch break, and even though we are outside, the smell of raw fish is everywhere. I wrinkle my nose. “Ewww, it smells.”

My mom corrects me. “That’s the smell of money.”

And there is money to be made, all right.

Last payday, half the cannery workers got paid for overtime work, and there was a closure for fishing after an exceptionally good run, which meant fishermen received advances as well—the banks in Prince Rupert ran out of money. All of them. Everyone in town was talking about it.

When my mom and I were walking down Third Avenue that day, we bumped into someone she knew.

“Did you hear about the banks?” they asked. “Were you able to cash your check?”

Thankfully, she had cashed it.

I notice adults often carry fifty- or hundred-dollar bills during the summer months, and you can tell it makes them feel good. Those rich brown and vibrant red bills are commonplace.

We preserve our salmon in the summer. Food fish, the adults call it. It’s a staple item that sustains us throughout the long winter months. Grandma always prepares ahead, well before she even gets fish. She gathers jars together to clean and then counts how many empty cases she has. If she happens to be short, she goes searching in our basement for more jars.

This is an adventure in itself, as you have to go outside, and the stairs leading down to our unfinished basement are overgrown with grass and a buildup of slippery moss.

Grandma is older and a bit heavier, and it shows in her movements. None of that deters her. Housedress and slippers on, she makes her way down there.

I follow along, as I know she needs the help. This time, the trek is worth it. “Ooh,” Grandma says, as her eyes shimmer at all the jars she finds. That’s mostly how she communicates—through her eyes.

Several of my cousins are at our house at any given time in the summer, while their parents are at work at the cannery. They’ve followed us to the basement and have gathered at the door. This pleases Grandma, as extra hands are always welcome. She starts to pass the Mason jars over to us grandkids one by one, and like an assembly line of little ants, we make our way back upstairs.

When someone from our reserve drops off a catch of sockeye salmon, Grandma is ready. She turns the kitchen table into a makeshift workstation by covering it with a flattened cardboard box.

Grandma is strong and has big arms and hands, but I can see removing the fish heads, then gutting and cleaning the fish isn’t an easy job.

I stand quietly observing, being sure not to get in the way.

The fish heads go to one pile, and if there are eggs inside, they go to another. Then she cuts the fish into even smaller sections, holding up a slab of salmon against a pint or quart jar, making sure the cut is the right size.

This time she lets me measure and pour the salt into jars. This is an important job, as the amounts have to be exact.

Then she wipes down the mouth of the jars, fastens the lids, and into the boiler they go.

Grandma keeps the fish heads for baking—she never throws them out. “Don’t waste seafood,” she often says to me. I’m used to her saying things like that. There are so many rules around not misusing or wasting our traditional foods.

The two of us eat the fish heads as an afternoon snack. My cousins would sooner play outside than eat fish heads. We don’t mind, more for us!

I sit at the kitchen table watching closely as Grandma pulls the baking pan out of the oven and carefully places it on the table. There are almost a dozen salmon heads on the thin pan. I stare at them curiously. Their eyes slightly bulged from the heat, their tiny little sharp teeth stillintact. I reach out to try and touch one of them.

Grandma reprimands me. “Don’t play with the fish.”

I think the fish heads are the best part of the salmon, very different from the rest. The meat inside is oily, and the texture silky-smooth. The only thing they need is a bit of salt. Grandma and I sit in our small kitchen not saying a word, eating our tasty fish heads until the meat of every last one of them is gone.

Grandma sets fish steaks aside to cook for dinner as well. I often hear adults say, “Fried fish is best when it’s fresh!” She coats the fish in flour and then fries the steaks in a cast-iron pan and serves it with white rice and store-bought sweet pickles on the side.

When my mom and aunties walk in the door, they can tell by the smell that they’re in for a delicious meal. Work uniform and kerchief still on, my mom digs in. “Luk’wil ts’imaatk,” she says.

It is very tasty. I don’t like the skin, though. I peel mine off with my fork, hold it up and ask, “Who wants my skin?”

My mom holds her plate toward me. I drop the piece of skin on it and she says, “That’s the best part.”

Grandma often shares fish with our non-Native neighbors as well. It’s probably her way of saying thank you to them for mowing our lawn. They don’t offer or ask to mow it—they just do it. After dinner, she asks me to go see if our neighbor could meet her at the fence between our houses.

My grandma mostly speaks in our Sm’algya̱x language, so when the father of the family next door reaches what’s remaining of our fence, they don’t say much. Grandma smiles with her eyes, he smiles and nods in return, and reaches over the fence to accept the big silvery sockeye from her.

Words aren’t necessary. The language of sharing salmon is simple.

About the Author

Kim Spencer is a graduate of the Writers Studio at Simon Fraser University, where she focused on creative nonfiction. Two of her short stories were published in an anthology released through SFU, and an experimental short story of hers appeared in Filling Station magazine. Kim was selected as a mentee by the Writers Union of Canada for BIPOC Writers Connect, as well as for ECW’s BIPOC Writers Mentorship Program. Kim is from the Ts’msyen Nation in northwest BC and currently lives in Vancouver, British Columbia.