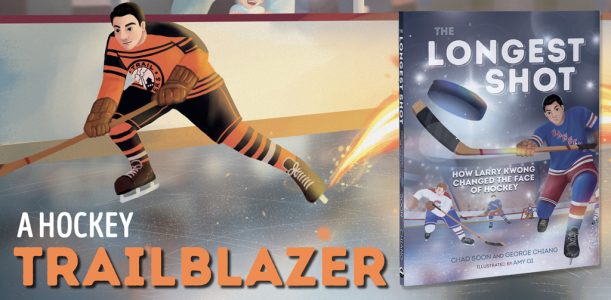

In 1948, Larry Kwong made history as the first player of Asian descent in the NHL when he played one shift with the New York Rangers. But even though Larry’s achievement happened more than 70 years ago, his contribution to hockey is only now being recognized.

The Longest Shot: How Larry Kwong Changed the Face of Hockey tells the story of how Larry broke hockey’s color barrier and fought racism and discrimination at every step of his career. Hear from co-authors Chad Soon and George Chiang on the inspiration behind the book and what they hope young readers will take away from Larry Kwong’s story.

Chad, you’ve made Larry Kwong’s story public and have continued to celebrate his life and legacy. What motivated you to share his story with the world?

CS: For me, this story goes back 40 years. I was a hockey-obsessed kid, and I remember my goong goong [grandfather] quietly telling me about his hero. After scouring hockey books and magazines for a mere mention of Larry Kwong, I came up with nothing. His story wasn’t there. I’d go play at the Nanaimo Civic Arena not knowing Larry used to blaze down the same ice.

Larry had a Hall of Fame career as a pioneer and a builder, yet he’s erased from history. One reason his incredible story got lost is that it isn’t a comfortable one for the hockey establishment. Larry made the giant leap to the big league, but then he was denied a real chance to show his ability. He was excluded. They weren’t ready for someone who looked like him.

Finally, in 2007, I found articles by Kenda Gee and Tom Hawthorn that detailed Larry Kwong’s seemingly impossible climb up the hockey ladder. At last it dawned on me what Larry represented. He had been a beacon of hope for my grandpa and so many other disenfranchised Chinese Canadians who’d lived their lives under a no-Chinese policy. Larry had broken barriers and moved the game and his society forward, but, at age 84, Larry was living in virtual hockey obscurity. It was upsetting.

Even in Larry’s hometown of Vernon, few knew his name anymore. Yet Larry was the city’s first NHL player—and on top of that he had broken hockey’s color barrier! There had been a few Indigenous trailblazers before Larry, but in 1948 the NHL was all white.

The first goal was to restore his hero status in Vernon. From there, it was about trying to spread the legend of Larry Kwong throughout the hockey world and everywhere else; you don’t have to be a hockey fan to appreciate his extraordinary life.

How did you first meet Larry?

CS: I first phoned Larry late in 2007. He had a listed number. I told him that he’d been a big inspiration for my grandpa and that I thought he was a big deal, too. He seemed surprised to hear that. I let him know that I’d try to get the hockey world to acknowledge the 60th anniversary of his NHL debut in March 2008. Nothing had been done for his 50th, and unfortunately not much more ended up being done for 60.

That summer my family moved from Toronto to Vernon. My wife and kids flew, and my dad and I drove. Larry invited us to visit him in Calgary. His daughter, Kristina, and I laugh about this now, but she was naturally worried about a random stranger from Toronto dropping in to see her elderly father. Larry welcomed us, and over Chinese tea and cookies he showed us his scrapbooks full of amazing photos, documents, letters and newspaper clippings. He was so warm and humble that I became even more determined to get him some kind of recognition.

What was the experience of getting to know your hockey hero (and your grandpa’s hockey hero) like?

CS: It was life changing. You hope your hero is a good person, but Larry turned out to be nicer than I could’ve imagined. But then, surpassing expectations is what Larry did his whole life. I have yet to see or hear a bad word about him from anyone who knew him.

We would talk on the phone every week. I’d visit him in Calgary whenever I could. He’d throw birthday parties at a Chinese restaurant for hundreds of guests, and we’d all come away with gift bags. I was also able to celebrate with Larry and his family as he received awards in places like Penticton, Vernon, Vancouver and Canmore. He accepted each with deep gratitude and with his self-deprecating sense of humor.

Larry had the special ability to make others feel special. He built people up. He took an interest in your life. He was appreciative and thoughtful, taking the time to write thank you cards and making sure my kids got treat bags after a visit. I miss his friendship. Luckily, I’ve become close with his family and, no surprise, they’re all-star people, too.

What are some lessons you learned from Larry?

CS: Larry faced many challenges in his life. How he dealt with all the adversity is quite the master class in resilience. He lost his father at age five. He and his family scraped by during the Great Depression. Growing up in a Chinatown in the wilds of British Columbia, Larry was light years away from the NHL, but he dared to dream anyway. As a Chinese Canadian, he was treated as a lesser person. He was the target of taunts, ridicule, hate and violence. Larry’s answer was to show his quality, defy stereotypes and break barriers with finesse and a smile.

That he made it all the way to the big league still seems unbelievable. I don’t know a story that better exemplifies the belief that anything is possible. That’s how my grandfather saw it. If a Chinese Canadian could do that, what couldn’t we do?

It’s a lesson in doing what you love, going after your goals, but also having a bigger purpose. It wasn’t just hockey glory that Larry dreamed of; he wanted a more inclusive society. Like Larry, we can use whatever special talents we have to try to make things better.

Why were you inspired to write The Longest Shot?

CS: For ten years I was focused on hall of fame nominations and trying to get Larry’s story out in different media. It took a call from George in 2017 to get me thinking again about the possibility of a book. I had just lost my grandfather, and I was working on a video presentation for his celebration of life. In less than a year, my father and Larry also passed away. Their life stories were connected. So, working on this project became a way for me to grieve these three huge role models of mine and keep their memories alive.

George had just published his first book, The Railroad Adventures of Chen Sing. I was inspired by that. It, too, was a children’s book. I knew firsthand that Larry’s underdog story really resonated with kids. I had been telling it to twenty-something new students a year. To keep his legacy going, we obviously needed to reach a wider audience than that.

George and I pitched a picture book. It was Orca editor Kirstie Hudson’s idea to make it a middle-grade biography. There hadn’t been one written about Larry. I was feeling the loss of Larry, and I was feeling that gap in the literature, too. It was nice to hear Larry’s voice again on my recordings. Writing his story was about remembering—and about claiming for Larry his rightful place in the history books.

What main takeaways do you hope for readers after they finish your book?

GC: Our aim was to tell Larry’s story and shed light on a period when racism pervaded not only the realm of hockey but also society at large. We hope that readers will learn that by doing your best, through unwavering determination and hard work, you can overcome anything to realize your dreams.

CS: In his review, Daniel Gawthrop writes, “By the time they finish this book, young readers of The Longest Shot will be left wondering: Why on earth has Larry Kwong been excluded from the Hockey Hall of Fame?” I’m pretty sure I squealed when I read that. Larry has not got the recognition he deserves. Not even close. But there’s a growing campaign to change that. My friend Chris Woo started a petition that has almost 12,000 people calling for Larry’s induction into the Hall of Fame.

My hope is that readers find a hero in Larry, too. We could certainly use more changemakers like him today.

What still needs to happen to make hockey a more welcoming and diverse sport?

GC: Promoting diversity in hockey would include empowering people of color in pivotal roles, including coaches, scouts, general managers and other team and league officials at all levels.

CS: Larry’s story can help! Larry was told he didn’t look like a hockey player. But he was one of the best. It’s important to show that diverse people have been contributing to the game for a long, long time. Larry made every team he was on better. He helped to grow the sport in Europe. One of the ways his legacy lives on is in the Larry Kwong Memorial Hockey 4 Youth program. Started by Moezine Hasham, Hockey 4 Youth is working across the country to remove the financial and cultural barriers that keep young people out of the sport. In Vernon, our group is made up of mostly new Canadian students, including refugees, but also Indigenous kids and others born here who were previously sidelined by the cost. We speak nine different languages, but all smile the same while playing this great game. Moezine’s motto is “The only barrier should be the boards.” I know Larry would have agreed with that!

Chad Soon is a fourth-generation Chinese Canadian. His parents encouraged him to do what he loved: draw, read and play hockey. Growing up on Vancouver Island, Chad dreamed of being an NHL star. He went as far as bantam house-league hockey before realizing that he wasn’t going to be the next Larry Kwong. Chad now teaches in Larry Kwong’s hometown of Vernon, British Columbia, where he realized another dream: writing this book.

George Chiang grew up loving and playing hockey in Etobicoke, Ontario. George is the composer of the internationally acclaimed musical Golden Lotus and the author of the children’s books The Railroad Adventures of Chen Sing and The Pioneer Adventures of Chen Sing. He has directed and/or produced award-winning music videos for his songs, including A World Away (Remix) and Old Montreal. George’s acting credits include roles in Eloise at the Plaza and McKenna Shoots for the Stars. He lives in Stouffville, Ontario.