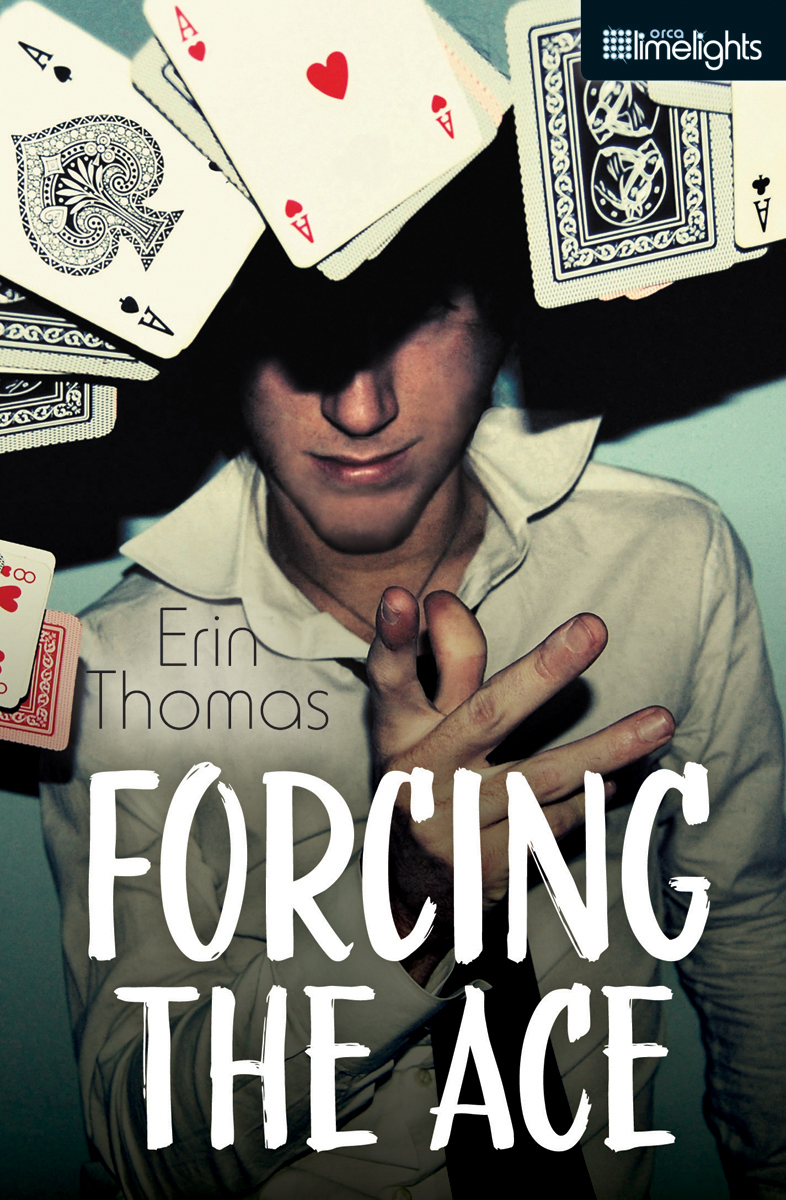

Erin’s most recent novel, Forcing the Ace, is a new addition to the Orca Limelights series—books for kids who love the performing arts.

—-

The other night I sat in a room with a handful of other writers here in my hometown. It’s a routine occurrence—we’re a writing group, and we meet at the library every second Tuesday. We all write in different genres and styles, we all bring different backgrounds and experiences to our writing, and we’re all there for one reason: To make the work better.

One of the things I found most fascinating in researching ‘Forcing the Ace’ (Orca Limelights, 2014) was that magicians do the same thing. The day I attended Sorcerers Safari Magic Camp in Ontario, I was lucky enough to sit in on a Performance Workshop led by professional magicians Aaron Fisher, Justin Flom and Bobby Motta. It took place in a pineboard hall with stacking chairs and a stage, and the participants, tracking in pine needles and swatting mosquitos, were teenaged magicians.

I learned more by watching that workshop than I did in months of research. More than that, I got a glimpse of what there was to know—all the things that magicians worry about that had never even crossed my mind as possibilities.

Up to that point, I’d been worrying about how tricks were done, trying to learn the secrets behind the magic. But learning to do the trick is one thing—that’s about technique and it’s about putting the hours in. Learning to perform the effect for an audience involves a whole new sort of work.

A scattering of overheard advice: “You have to make do with the situation you have; the audience might not be exactly where you want them.” “Once you get your 1000 shows done, there’s a comfort that will set in.” “Doing close-up magic for parlour, move around more. Your stage is as big as you make it.” “Look for one clear, effective moment in a trick; take one little beat and own it.” “Don’t script action.” “Slow down. We magicians get so used to doing magic, we forget how long it takes to SEE it.”

And two ideas that I loved so much I stole them for my book: “Bring the audience in; connect them into your web.” “There’s a habit all cardmen have, of doing a lot of riffling and dribbling all the time. If you pull out your deck, that’s because you’re gonna shoot it.”

The magicians had their own vocabulary for talking about performance. They discussed things like how you want your audience volunteer to feel—it’s great to get laughs, but risky if they’re at the volunteer’s expense. They talked about timing and about trimming back the words around the effects to let the magic shine through. It was a peek behind the curtain, and it fascinated me. It also resonated in a very clear, very obvious way.

“Have you thought about present tense for this part?” “There’s a disconnect here, between the age of the narrator and the voice.” “These parts start with story, and that pulls the reader in. Here it’s more of a list. Go with the story starts, they’re working better.” “Lose the passive voice.” “Ask yourself what in the story is fascinating you—that’s what will pull in the reader.”

Someone sitting in on my writing group’s “performance workshop” the other night might have heard comments like these.

In both cases, critique is encouragement. It’s honest talk among people who care deeply about the craft behind what they’re doing. And in both cases, I suspect, it can sting a bit, but you come away grateful for what you’ve learned.

I think the kids at magic camp win out for guts, though—it’s one thing to share your writing with long-standing friends, but much harder to get up and perform a piece of magic in front of three of your idols.

—-

For more information about Forcing the Ace or to learn more about the Orca Limelights series, visit the website.