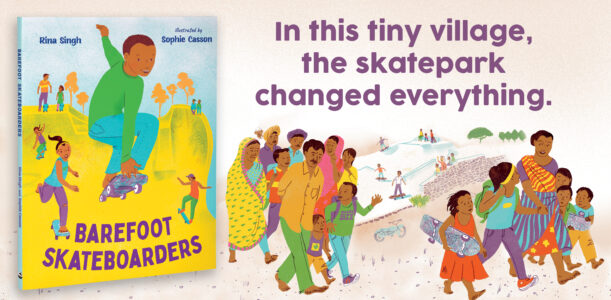

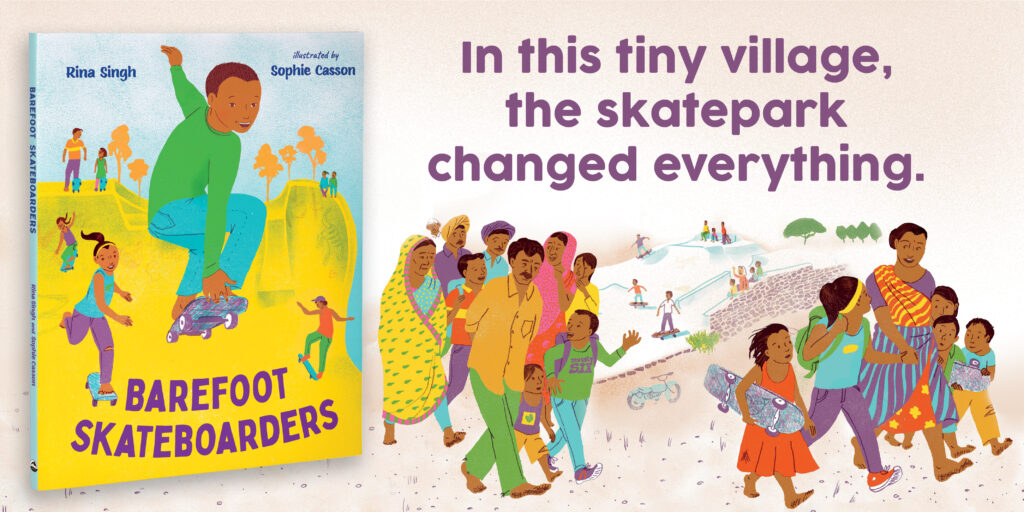

In Rina Singh’s new nonfiction picture book, the tiny village of Janwaar in Madhya Pradesh, India, gets a new skatepark, which inspires Ramkesh and all the local kids to learn how to skateboard, putting them on the map and uniting their community. Hear about the inspiration behind the story and what Rina hopes readers will take away.

You have a personal connection with the barefoot skateboarders you write about in your picture book! How did you come to meet them (and did you try skateboarding with them)?

Yes, I do! In 2018, I spent four glorious days in Janwaar and watched the little barefoot skateboarders ripping up the skatepark. Earlier that year, I had met Ulrike Reinhard, a German activist, in Delhi. Inspired by the success of Skateistan in Afghanistan, she started Janwaar Castle in this rural village in Madhya Pradesh, India.

In 2014, she asked fifteen artists worldwide, including Ai Weiwei, to transform skateboards into artboards. The boards were auctioned as a fundraiser, and she built the skatepark with the proceeds. Twelve skateboarders from six different countries, including multiple world champion Nyjah Huston from California, volunteered to design and construct the park with the locals. An incredible story of social, cultural and economic change unfolded. Ulrike did not coach the children because she’s not a skateboarder. Instead, children are the driving force. Empowered by the skills of skateboarding, they became the actual changemakers.

I was so excited to hear about what was happening in Janwaar that I planned to see for myself. I returned to India later in the year, took an overnight train from Delhi to Khajuraho, and then a taxi to Janwaar. After touring the village and seeing the kids’ brilliant skateboarding skills in action, I visited their homes and talked to their mothers. Ramkesh’s mother unwrapped a piece of yellow cloth and proudly showed me her son’s passport. He beamed as his mother spoke of his achievements as a skateboarder. Skateboarding has given the villagers an identity and a new sense of pride.

The joy I saw on the faces of the children inspired me to write the story.

Yes, I tried skateboarding but gave up because I was afraid of breaking any bones. I wish I had the opportunity as a kid to try it.

What did your process for writing the book look like? How does writing a nonfiction picture book differ from writing a fictional picture book?

Writing a nonfiction picture book differs significantly from writing a fictional picture book in several ways:

When I write a nonfiction picture book, I start with real-life events, people or concepts. Research is a crucial part of the process. I need to gather accurate information, verify facts and ensure that the story I tell is both truthful and engaging. For my book about the barefoot skateboarders in Janwaar, I had to delve into the history of the skatepark, understand the background of Ulrike Reinhard’s project and capture the real-life experiences of the children and their community.

Nonfiction requires a careful balance between being informative and maintaining the reader’s interest. I have to present facts in a way that is accessible and exciting for young readers. This often involves finding a narrative thread or a compelling way to structure the information. For example, in Barefoot Skateboarders, I focused on the transformative journey of the children and how skateboarding brought positive change to their lives and community.

On the other hand, writing a fictional picture book allows for more creative freedom. I can invent characters, settings and plots that come entirely from my imagination. The challenge here is to create a story that resonates emotionally with readers and feels believable within its own world. The narrative arc, character development and imaginative elements are key components that drive the story.

While both types of books aim to captivate and engage young readers, nonfiction demands a higher level of accuracy and responsibility in portraying real events and people.

What was your favorite part about writing the book?

My favorite part of writing Barefoot Skateboarders was revisiting my memories of Janwaar. I couldn’t believe I flew all the way to India and then made the journey to Janwaar to capture the spirit of the children and their community.

One moment that stood out to me was my interaction with Ramkesh’s mother. I vividly remember the pride in her eyes as she unwrapped a piece of yellow cloth to reveal her son’s passport, a symbol of his achievements and the opportunities skateboarding had brought into his life. Writing about this moment allowed me to relive the joy and pride I felt during that encounter. It was a powerful reminder of the profound impact that skateboarding had on the villagers, giving them a new sense of identity and pride.

Another favorite part was that while the story was brewing in my head, for almost a year I taught English to Janwaar kids on Skype. I used to look forward to my Sunday morning sessions with them. Ulrike Reinhard’s vision inspired by Skateistan in Afghanistan to the collaborative effort of artists and skateboarders from around the world touched me deeply.

Writing Barefoot Skateboarders gave me the opportunity to share an incredible story of transformation, resilience and the power of community. It truly is a privilege to tell the story of the Janwaar children and to highlight how something as simple as skateboarding could bring about such significant social and cultural change.

What is something that you learned from the barefoot skateboarders?

Spending time with these young skaters, I saw firsthand how they overcame challenges and embraced new opportunities with incredible enthusiasm and courage.

Despite the limited resources and the resistance from their own families and community they faced, the children of Janwaar pursued their love for skateboarding with unwavering passion. They mastered impressive skills and brought positive change to their village.

Ulrike Reinhard did not coach the children because she wasn’t a skateboarder herself. Instead, the children became the driving force behind their own progress. They taught each other, supported one another and grew together as a community. This experience highlighted the importance of giving individuals the tools and freedom to discover their own strengths and capabilities.

There is one thing that I learned from Ulrike that I will never forget. The villagers were so poor that most children only had one set of clothes and most of them were barefoot. She could easily have fundraised and offered them new clothes or shoes. But she never did. That was not the purpose. What she offered them was far more valuable.

My belief that changes often starts at the grassroots level was also reinforced. The skatepark project began with a simple idea and a small community, yet it led to profound social, cultural and economic changes.

What main takeaways do you hope for readers after they finish your book?

I hope readers understand the power of passion and perseverance. The children of Janwaar, with their boundless enthusiasm for skateboarding, showed me that when you truly love something, you can overcome any obstacle. I want readers to see that their own passions can drive them to achieve amazing things, no matter the circumstances.

The skatepark in Janwaar was a product of collective effort—artists, skateboarders and villagers coming together to create something beautiful and transformative. I want readers to appreciate how working together can bring about positive change and how we can all support one another in our efforts.

The children in Janwaar were given the freedom to learn, grow and lead. They became the change makers in their community. I hope readers feel inspired to take charge of their own lives and believe in their ability to make a difference, no matter how young they are.

Any meaningful change often starts small. The story of Janwaar Castle began with a simple idea and a lot of heart. Finally, I hope readers come away with a sense of joy and hope.

What’s next for you? Do you have any other books in the works?

Coming out next year is Bird Brothers: A Delhi Story. It is an incredible story of human kindness towards a neglected predatory species.

These majestic birds of prey, so crucial to the city’s ecosystem, are threatened by the glass-crusted string of the paper kite, extreme heat and toxic air. And no one cares whether these birds live or die. The brothers have treated more than 26,000 injured birds in the last twelve years. And 80% of the birds that underwent wing surgery took to the skies again.

I was totally humbled when I met the brothers in Delhi last year.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I hope you read the book and get to know the barefoot skateboarders!

Rina Singh is an award-winning children’s author who is drawn to real-life stories about the environment and social justice. Her critically acclaimed and award-winning books include Grandmother School, winner of the 2021 Christie Harris Illustrated Children’s Literature Prize; Diwali: A Festival of Lights, nominated for the Red Cedar Award; and Once, a Bird. Rina has an MFA in creative writing from Concordia University and a teaching degree from McGill University. She lives in Toronto.